Story Points, Velocity, and Engineer Productivity

2020-02-08; published 2021-12-31

I recently asked some engineering managers that I am acquainted with about how they handle story points: Do they think it's best to connect story points to a particular unit of time? And if not, how do they use story points to provide usable metrics? We compared some notes, and this article is the result / outcome / summary of those conversations as well as my own experiences working with a variety of engineering teams.

Story Points

Story points are used in software engineering as a tool to estimate the amount of effort that a particular task will take to complete, from start to finish. Story points can be very useful to a team, its managers, and the clients:

- You estimate how much work (how many points) a project will take to complete.

- Then you track how much work you complete per iteration (a repeating amount of time — say, every 2 weeks).

- With this information, you can estimate how long it will take to finish the project.

- If the requirements change (as they usually do) or your task estimates change, then your estimated completion time will change.

- If your team composition changes (usually more slowly than requirements), then your velocity will change, and the estimated completion time can be re-calculated.

Story points create a great conversation framework for discussions between customers / business owners, project managers, and developers.

- Customer/Owner: I'd like to make this little change.

- Developers: Okay, we'll estimate it and get back to you … [Later] We estimate that change as requiring X points.

- Project manager: Let's see, based on our average project velocity, that means the project will take Y weeks longer than we anticipated.

- Customer/Owner: Hmmm, I don't want it later.

- Project manager: Okay, what are you willing to drop from the project requirements to make that work?

- Customer/Owner: Why don't you put more people on it?

- Project manager: We could do that. We would need to hire someone, onboard them, and then reassess our velocity. I can't guarantee that doing that will positively impact the project schedule, and it might slow things down further, because hiring and onboarding takes everyone's time.

Story Points as a Measure of Work

Story point are a way of measuring the value or amount of work that developers have completed. What is the best measure of development work?

Let's suppose that we have a project with a number of features. Each of these features requires implementing a certain amount of working, tested, peer-reviewed code that passes all tests and can be merged into the main development branch. For each feature, we can make an estimate based on the amount of code, its complexity, and its uncertainty.

- The amount of code to be written is directly related to the size of the feature to be implemented, which (all else being equal) tells us how much work it will be to implement.

- The complexity of the feature has a direct impact on how much work it will be to implement: More complex features take longer to implement, even if the amount of code is the same.

- The uncertainty of implementing the feature means that it might take more or less work to implement. If a feature is more uncertain, then we should add some work to the estimate to cover that uncertainty. (If the uncertainty is too great, we should do a spike to investigate and resolve our questions, then re-estimate the task. But most of the time adding a bit of uncertainty factor to the estimate is more efficient.)

For a given feature, when we understand the amount and complexity of the code to be implemented, along with the uncertainty in implementing it, we are in a good position to understand the amount of work that feature will require to implement. The question is, how do we convert our understanding of the feature into numbers that can be used for tracking purposes?

Estimating Story Points

When we estimate story points for a feature, we need to convert our qualitative understanding of the feature into a measurement — a number of points. There are two ways to do this:

- Estimate the amount of time it will take to implement the feature, and assign each point a fixed amount of time. X time = Y story points. Easy. Right?

- Estimate the amount of work this feature will require relative to other features, and assign points based on this relative scale. Feature A is twice as big/complex/uncertain as Feature B, so it gets twice as many points.

On the face of it, option #1 seems a lot more straightforward. So why not do that? To answer that question, let's see how it might work out in practice.

Time-Based Story Points

Let's suppose we have three developers on our team: Alice (the rock star) is a senior developer who quickly writes correct, performant code that meets all requirements for the feature she is implementing. Bob (the bungler) is as experienced as Alice, but he's not as smart or careful, so it takes him twice as long to finish the same feature as Alice, and sometimes he has to make significant changes during code review, such as adding missed test cases and getting his feature to pass all the automated checks on the continuous integration (CI) server. Then there's Chris (the junior developer), who usually takes five times as long as Alice to finish implementing the same feature, and twice as long as Bob to pass the testing and review phase.

Why not just assign story points a particular amount of time? It's simpler, isn't it? Not really, and it's unreliable, for three reasons:

- No developer can accurately estimate their own time in advance (see Further Reading). We usually wildly underestimate the amount of time a software development task will take. But sometimes we are pleasantly surprised when a task we thought would take a week turns out only to require a day. The longer the time frames involved, the more wildly wrong our estimates are.

- Every developer estimates time differently based on their own skill and experience. No two developers are exactly the same, so their time estimates cannot agree.

- How will Alice, Bob, and Charlie agree on a time estimate for any feature or task in their project?

- If each developer provides their own time estimates, then how will we know that Alice is 2~3 times more productive than Bob and 5~10 times more productive than Charlie?

- Developers who are trying to protect themselves from managerial or customer time pressure will sometimes pad their time estimates. It happens.

In short, developer time estimates are unreliable. If we rely on developers' time estimates, then we won't really understand the project's velocity, we won't have any measurable insight into the relative value of each member of the team, and our project completion estimates will be wrong.

Relative-Effort Story Points

Thankfully, we don't ever need developers to make time estimates for their tasks in order to obtain accurate analytics of important measures like individual and team velocity, estimated project size, and estimated project completion date.

Instead, we just need developers to accurately rank how much effort a particular feature will require relative to other features in the list: Does this feature require more, less, or approximately the same amount of effort as the other features?

Here's how it works: Instead of asking developers to estimate tasks in terms of time, we ask developers to estimate the amount of work required to complete a task by comparing it to other tasks that they have done and are doing. Then, rather than assigning time values directly to tasks (which developers cannot know), we use the following rules:

- The smallest trackable task is 1 point. In other words, 1 point = 1 unit of work. We can't break it down further, so it is assigned the value of 1.

- The value of all other tasks is relative to the smallest, most basic task. A task that is twice as much work as the smallest task is 2 points. A big task might be 5 points. A task that is between the 2-pointer and the 5-pointer would be 3 points.

- The value of all tasks are ranked as being larger, smaller, and approximately the same as other tasks. Development teams become very good at understanding whether a given task requires more, less, or equal work as compared with other tasks.

It is common practice to limit the number of point values available to choose from, since having more than 5 or 6 choices becomes unmanageable in practice. It is most common to use the sequence {1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13}, which provides fine-grained choices for small tasks and only a few spread-out choices for larger tasks. This limitation might seem to lead to inaccurate estimates, but in practice allows our work estimates to be accurate enough for all useful purposes, and it allows the development team not to get bogged down in the difference between a 4 or 5 point task.

- Any task that is larger than an agreed-upon maximum has to be broken down into smaller tasks. The maximum is usually around 8 to 13 points.

Let's compare these "relative story points" (point value based on comparison between tasks) to time-based story points in terms of reliability and accuracy (each of the following list items corresponds to the time-based list above):

- Unlike with time estimates, developers can accurately estimate a task's size, complexity, and uncertainty in relation to other tasks they have done.

- Developers can agree on point estimates, if the points are a measure of the relative value of tasks. They can agree, for example, that one task is 2 times more work as some other task.

- Developers probably won't pad the point estimates if the points are not tied to time — padding won't work, because project completion estimates and productivity measures will be just as accurate, and will in fact be the same just with different numbers.

It turns out that developers are much better at estimating and ranking relative work effort than they are at estimating work time. In other words: Points based on estimated work effort are much more reliable than points based on estimated work time.

Stable Points: Task Estimation as a Team Exercise

For relative-value story points to work well, it is important that their value be stable. To achieve stability, we play a game together that we might call "Task Estimation" (often pronounced "project estimating" or "backlog grooming" or "sprint planning"). This game has the following procedure:

- The development team discusses every task until we all understand its (a) size, (b) complexity, and (c) uncertainty.

- Each member of the team assesses each task relative to all other tasks (as explained above). Then we vote together (and simultaneously) on the point value of each task.

- Everyone on the development team has to agree on the point value for each task. If we don't yet agree, then we don't yet understand the task well enough. (Simultaneous voting ensures that remaining uncertainty and disagreement is exposed — not to apply social pressure to the outliers, but as a flag to investigate the issue further.) So we discuss the task further — we revisit questions of size, complexity, and uncertainty — and we re-vote. Any small remaining disagreement is resolved by taking the larger value.

By playing the "Task Estimation" game regularly (at least once per iteration), the team will quickly come to consensus on what their story points mean (as a relative measure of work). And so the value of the points will be stable.

Measuring Velocity and Productivity

Now we have story points for all of our tasks. How can we use these story points to track individual and team velocity and to estimate the project completion date?

Answering this question goes back to the basic usage of points to track work completed.

- Every task has an estimate in points based on the amount of work required.

- Every iteration, you track not just which tasks were completed, but who completed which task (good task tracking software will do this automatically).

- You can therefore calculate how many points not just the team as a whole, but also each person on the team, has completed in each iteration. You can, in short, measure the productivity of each team member relative to all the others.

For example: After a couple of iterations of the development cycle, you see that Alice completes 12 points per iteration, Bob averages 7 points, and Charlie is lucky to finish 3. That information is actionable intelligence for managers.

Once our story points have a stable value, those points can be used to accurately measure / estimate:

- The value of the total project and each of its tasks (number of points)

- Individual and team velocity (number of points per iteration)

- Project milestone completion date (points remaining divided by velocity).

- Individual productivity (individual velocity compared to team velocity)

Each of these measures / estimates can be made available in business and management reports, providing actionable intelligence.

An Example Project

Here are a couple of report charts from a recent project I've been involved in.

Project Burndown Chart for a Recent Project Iteration

The velocity for that three-week iteration was 20 points.

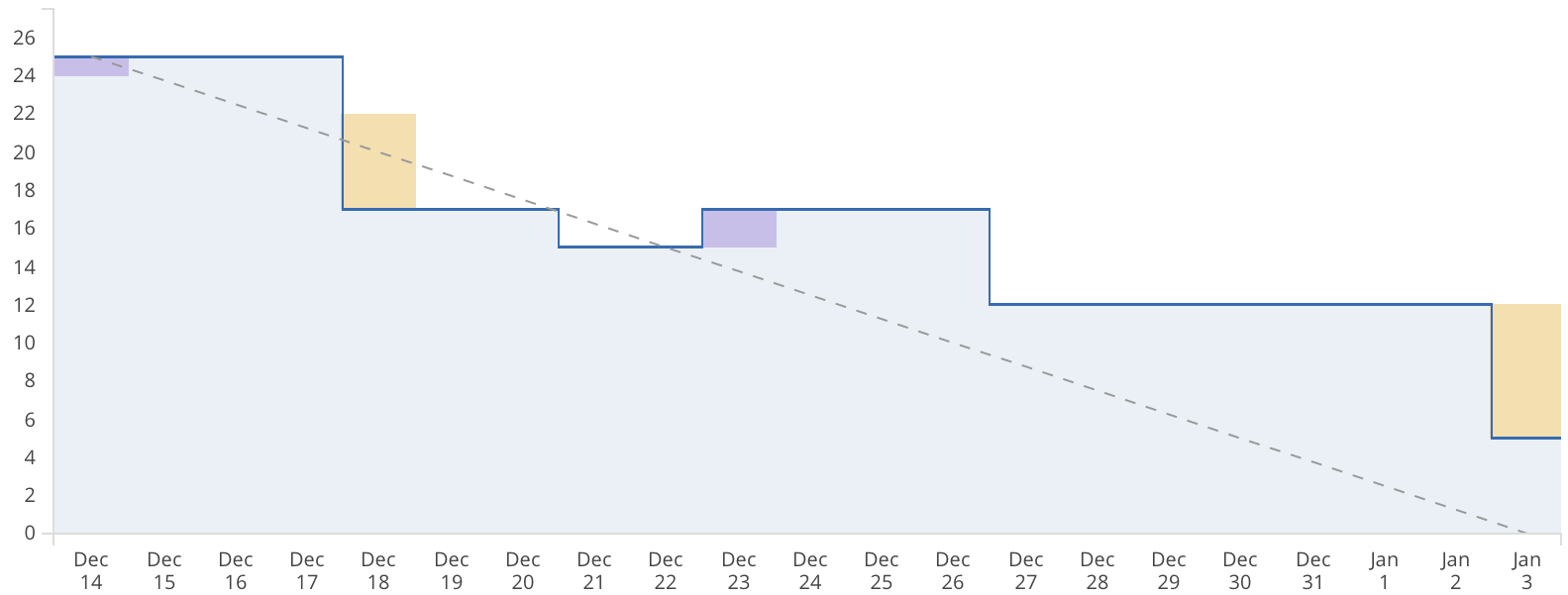

Burndown Chart for the Whole Project

The project team made steady progress on this particular project in October and November, got a lot done in December, but was focusing more on other projects in January while this project was being reviewed by the customer. We can now finish the project by the end of March if we work at least at the average pace of the past 4 months.

Project Velocity per Week

This chart shows clearly how the team's velocity on this project has changed each week — it shows the project kickoff, steady progress in October and November, great progress in December as we put in extra hours to complete a milestone before Christmas, and very little progress in January while the customer was reviewing the project and doing market testing.

As you can see, these reports provide actionable intelligence: They help the customer, project manager, and developers see the project status and make appropriate changes.

Use Good Tools

To use story points effectively, you need good tools. I've had good success with clubhouse.io: It has excellent and very usable tools for doing this work, and it scales nicely to many complex projects and large teams.

I have also used Jira for team and project tracking. Jira is much more mature (older) than Clubhouse. It includes more reports, and a lot more warts.

There are certainly other tools that can serve these roles — for example, GitHub and GitLab issues. The important thing is to use tools that give you access to the data, so you can develop reports that the tools themselves don't provide.

The Meaning of Story Points (and Dollars)

You can skip this section if you don't care about philosophy.

What do relative-value story points mean? If points aren't tied to a specific amount of time, How do you know that they have any meaning?

Relative-value story points are based on the inherent properties of the software development tasks themselves: The smallest trackable task is 1 point, and every other task is relative to that.

This feels too squishy to a lot of people. So let me draw on an analogy: What is a dollar? What does "one dollar" mean? How is its value determined? What is it based on?

Before 1933, one dollar was backed by 0.05 oz of gold stored in Fort Knox. But that changed in 1933. Since then, "one dollar" does not mean "X amount of gold." There is no longer any fixed relationship between gold and dollars.

So what is a dollar? The best answer I know of is:

A dollar is a unit of value that represents a certain amount of buying power.

A dollar's buying power (and therefore value) is stable, and it is agreed upon by some sort of consensus, such as the market and/or the Federal Reserve. (Stable, but not fixed: In college, I paid $5 for a sandwich that now costs $10, but wages are higher and dollars are smaller, so the result is a similar value. The change happened slowly. Economies only really suffer from this not-fixed arrangement when the value of the currency is unstable and changes too quickly.)

This definition of dollars might seem too squishy, but it's accurate to the world we live in. Also, dollars work fine in practice. We all know what a dollar is, at least in terms of being able to use it to live our lives: It's the amount we pay and are paid for goods and services. We don't trouble ourselves about existential questions like, "What is the meaning of a dollar?" — Those questions are unimportant to most of us most of the time. (Economists, central bankers, gold bugs, and other armchair philosophers are the exception.)

What matters is that we can use dollars to conduct transactions, which only requires that dollars should have a stable value that we all agree on, in relation to goods and services.

(We might disagree about the value of a good or service, but that's a different matter. In an economy with a stable currency, no buyer negotiates price by saying, "Actually, dollars are worth more today, haven't you heard? So I should pay you fewer dollars.")

As with dollars, it doesn't matter exactly what story points mean, it only matters that:

- Their value is agreed upon by those who use them.

- Their value is stable in correlation to a given amount of value.

If those two elements are in place, then story points can be used to track project development, just as dollars are used to track financial transactions.

Summary

To make best use of story points to track software development projects and teams, one should:

- Guide the development team in creating their own point estimates of the tasks in their project, based on the value (size, complexity, uncertainty) of each task relative to other tasks.

- Track point completion velocity per iteration for the team. Use that velocity and the remaining points to estimate a completion date. Make business decisions accordingly.

- Track point completion velocity for each developer. Use that velocity to measure developer productivity. Make management decisions accordingly.

- Use good tools, so you can track and measure work on your team's projects and use those analytics to make management and business decisions.

Conclusion

Although it might seem like a logical choice to assign a fixed-time value to story points, it is counter-productive to do so. Instead, it works well in practice to teach development teams to assign relative-value story points based on the estimated work required to complete each task. These practices give each team story points with stable values that we all can agree on (per team), which makes it possible to create accurate analytics of individual and team productivity, and accurate estimates of project completion time frames.

There are some excellent non-quantifiable benefits of these practices as well. I have seen in practice how story points and the estimation game help teams mentor each other and grow together to become outstanding engineers. I am convinced that the application of these principles is why some engineering groups have such consistently high-quality engineers.

Further Reading

What are story points? https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/what-are-story-points

Why Your IT Project May Be Riskier Than You Think. https://hbr.org/2011/09/why-your-it-project-may-be-riskier-than-you-think

Why Software Development Time Estimation Doesn't Work and Alternative Approaches. https://www.innoarchitech.com/blog/why-software-development-time-estimation-does-not-work-alternative-approaches

Why Asking Software Developers for Time Estimates Is a Terrible Idea and How to Bypass It. https://www.romenrg.com/blog/2015/09/28/why-asking-developers-for-time-estimates-in-software-projects-is-a-terrible-idea-and-how-to-bypass-it-with-scrum/

What is Scrum? https://www.atlassian.com/agile/scrum

The Scrum Guide. https://www.scrumguides.org/scrum-guide.html